Irish Independent, by Stella O'Malley

February 19 2023, A modern medical scandal: What really went wrong at the UK's controversial Tavistock gender clinic? - Independent.ie

The journ*list Hannah Barnes first learnt about issues at the Gender Identity Development Services (Gids) in the Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust in London when she was a journ*list reporting on the issue for Newsnight at the BBC.

As she delved into the details, she felt compelled to write Time to Think: The Inside Story of the Collapse of the Tavistock's Gender Service for Children, an exposé that brings us deep inside the murky world of psychologists who fast-tracked thousands of children onto a potentially unnecessary medicalised pathway.

Barnes opens the book with a gripping timeline of events that details a series of raised concerns, complaints, court cases and missed opportunities.

There was a fundamental flaw within the service as it was never clarified whether clinicians should operate from the basis of a belief in gender identity theory, which argues that adults should facilitate the transition of every child who wants it, no matter what age, or if they should take a developmental model of understanding, where medical transition is just one of many ways to alleviate gender-related distress.

The first concerns about Gids were raised by the psychoanalyst Sue Evans in 2005, however the subsequent report was filed and ignored for 15 years.

Then, roughly ten years ago, the demographics suddenly changed and all across the world there came a sudden, unexplained and unprecedented influx of teenage girls presenting with gender-related distress.

As the numbers grew, Gids became a major source of income for the Tavistock and, from initially being a tiny outlier operating out of not much more than a broom cupboard, by 2020-2021, combined adult and child gender services accounted for a quarter of the Tavistock's income. One clinician described how it was run more like "a tech start-up" than a clinical care centre.

Considerable pressure was exerted on Gids by lobby groups such as Mermaids, which was quick to level accusations of 'transphobia' whenever reluctance was shown.

Ultimately, over a thousand children were prescribed puberty blockers. Puberty blockers stop all sexual development in a growing child and promise, as the title of the book suggests, "time to think". However this is experimental treatment and the first results of the research carried out at Gids showed that puberty blockers demonstrated a statistically significant increase in statements about self-harm and suicidal ideation, and an increase in behavioural and emotional problems for natal girls.

Moreover at least 98pc of children on puberty blockers move on to cross-s*x hormones. Critics believe that blockers effectively 'lock in' children to a medicalised identity. In one case study, 'Harriet' shows how she experienced a "honeymoon period" when she first came out as trans.

It is often noted that a diagnosis of gender dysphoria can inappropriately overshadow all other issues and, even though Harriet was self-harming, experiencing suicidal thoughts and had a difficult relationship with food, her referral to the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (Camhs) was dismissed in favour of her appointment at Gids.

Although she didn't ask for them, Harriet was offered puberty blockers at the first appointment, and then twice more across five appointments.

At 18 years old, she was approved for testosterone at her first appointment in the adult services. Her voice deepened and hair started to grow on her jaw and elsewhere. She underwent a double mastectomy aged 19. Then some doubts crept in. As is often the case for females who take testosterone, s*x was painful and she became prone to urinary infections.

Harriet came to realise she was a female and a lesbian.

She subsequently stopped taking testosterone and detransitioned. She now has to shave daily and has a permanently deep voice. She describes the experience like "waking up from a nightmare or regaining control of my body after someone else took over".

Barnes devotes an entire chapter to Gids in Ireland. In 2012, Gids first started seeing Irish children as part of the 'Treatment Abroad Scheme'. The numbers quickly catapulted and it was decided to stop flying children over to London; instead, from 2015, Gids ran monthly clinics in Crumlin Children's Hospital. Curiously, the scheme continues to fund this service.

The waiting lists in both Ireland and the UK became unconscionably long as lobby groups promoted the idea that only gender specialists could work with gender-distressed children. Gids clinicians became overwhelmed, with some complaining about a caseload of as many as 140 patients each.

A series of raised concerns, meetings, formal and informal complaints were summarily dismissed. Sonia Appleby, child safeguarding lead at the Tavistock, ended up lodging a whistle-blowing claim against Gids which she subsequently won in November 2021.

In August 2018, an extensive report submitted by Dr David Bell, consultant psychiatrist at the Tavistock, branded Gids "not fit for purpose". By then, some children were being prescribed puberty blockers within the first 20 minutes of their first session.

Many staff left. In July 2019, the psychologist Dr Kirsty Entwistle left the service by publishing a 2,700- word open letter to Gids director Polly Carmichael expressing concerns about traumatised, deprived, and sexually or physically abused children being inappropriately referred for puberty-blocking treatment.

Finally, in July 2022, 17 years after the first whistle was blown, the NHS announced that Gids would be closed by spring 2023 and replaced by regional centres with a greater focus on mental health. Barnes notes that Sweden, Finland and France have also recently concluded that the perceived benefits of puberty blockers do not outweigh the risks.

The situation in Ireland replicates the whistle-blowing that happened at the Tavistock. Barnes describes how clinicians at the adult National Gender Service first raised concerns in 2018 about the "clearly mentally unwell" patients transferring from the children's services in Crumlin to the adult services in Loughlinstown.

In 2019, Dr Paul Moran and Professor Donal O'Shea, both highly experienced clinicians who have helped adults medically transition for over two decades, conducted an audit of 18 referrals of Gids patients that offered accounts of young people presenting with self-harming behaviour, depression, suicidality, eating disorders, traumatic life circumstances, and a disproportionately high number of people with autism.

Dr Moran expressed his concern to Crumlin that the Gids service was "unsafe and substandard" and called for the contract to be "terminated with immediate effect". Crumlin is currently "exploring the availability of the service in other EU jurisdictions", however according to Prof O'Shea, the current situation is "awful" and he blames "institutional laziness".

Barnes's compelling account of the downfall of Gids demonstrates how pressure groups can lead well-meaning clinicians to make increasingly ill-advised decisions. Time to Think is a devastating and shocking read, a salutary tale that shows how medical scandals can happen in plain sight and complaints are ignored when nobody is quite sure about their actual position on the issue.

The Observer, by Rachel Cooke

February 19 2023, Time to Think by Hannah Barnes review -- what went wrong at Gids? | Society books | The Guardian

Hannah Barnes's book about the rise and calamitous fall of the Gender Identity Development Service for children (Gids), a nationally commissioned unit at the Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust in north London, is the result of intensive work, carried out across several years. A journ*list at the BBC's Newsnight, Barnes has based her account on more than 100 hours of interviews with Gids' clinicians, former patients, and other experts, many of whom are quoted by name. It comes with 59 pages of notes, plentiful well-scrutinised statistics, and it is scrupulous and fair-minded. Several of her interviewees say they are happy either with the treatment they received at Gids, or with its practices -- and she, in turn, is content to let them speak.

Such a book cannot easily be dismissed. To do so, a person would not only have to be wilfully ignorant, they would also -- to use the popular language of the day -- need to be appallingly unkind. This is the story of the hurt caused to potentially hundreds of children since 2011, and perhaps before that. To shrug in the face of that story -- to refuse to listen to the young transgender people whose treatment caused, among other things, severe depression, sexual dysfunction, osteoporosis and stunted growth, and whose many other problems were simply ignored -- requires a callousness that would be far beyond my imagination were it not for the fact that, thanks to social media, I already know such stony-heartedness to be out there.

Gids, which opened in 1989, was established to provide talking therapies to young people who were questioning their gender identity (the Tavistock, under the aegis of which it operated from 1994, is a mental health trust). But the trigger for Barnes's interest in the unit has its beginnings in 2005, when concerns were first raised by staff over the growing number of patient referrals to endocrinologists who would prescribe hormone blockers designed to delay puberty. Such medication was recommended only in the case of children aged 16 or over. By 2011, however, Barnes contends, it appeared to be the clinic's raison d'etre. In that year, a child of 12 was on blockers. By 2016, a 10-year-old was taking them.

Clinicians at Gids insisted the effects of these drugs were reversible; that taking them would reduce the distress experienced by gender dysphoric children; and that there was no causality between starting hormone blockers and going on to take cross-s*x hormones (the latter are taken by adults who want fully to transition). Unfortunately, none of these things were true. Such drugs do have severe side effects, and while the causality between blockers and cross-s*x hormones cannot be proven -- all the studies into them have been designed without a control group -- 98% of children who take the first go on to take the latter. Most seriously of all, as Gids' own research suggested, they do not appear to lead to any improvement in children's psychological wellbeing.

So why did they continue to be prescribed? As referrals to Gids grew rapidly -- in 2009, it had 97; by 2020, this figure was 2,500 -- so did pressure on the service. Barnes found that the clinic -- which employed an unusually high number of junior staff, to whom it offered no real training -- no longer had much time for the psychological work (the talking therapies) of old. But something else was happening, too. Trans charities such as Mermaids were closely -- too closely -- involved with Gids. Such organisations vociferously encouraged the swift prescription of drugs. This now began to happen, on occasion, after only two consultations. Once a child was on blockers, they were rarely offered follow-up appointments. Gids did not keep in touch with its patients in the long term, or keep reliable data on outcomes.

A lot of this is already known, thanks largely to a number of whistleblowers. Last February, the paediatrician Dr Hilary Cass, commissioned by the NHS, issued a highly critical interim report into the service; in July, it was announced that Gids would close in 2023. But a lot of what Barnes tells us in Time to Think is far more disturbing than anything I've read before. Again and again, we watch as a child's background, however disordered, and her mental health, however fragile, are ignored by teams now interested only in gender.

The statistics are horrifying. Less than 2% of children in the UK have an autism spectrum disorder; at Gids, more than a third of referrals presented with neurodivergent traits. Clinicians also saw high numbers of children who had been sexually abused. But for the reader, it is the stories that Barnes recounts of individuals that speak loudest. The mother of one boy whose OCD was so severe he would leave his bedroom only to shower (he did this five times a day) suspected that his notions about gender had little to do with his distress. However, from the moment he was referred to the Tavistock, he was treated as if he were female and promised an endocrinology appointment. Her son, having finally rejected the treatment he was offered by Gids, now lives as a gay man.

As Barnes makes perfectly clear, this isn't a culture war story. This is a medical scandal, the full consequences of which may only be understood in many years' time. Among her interviewees is Dr Paul Moran, a consultant psychiatrist who now works in Ireland. A long career in gender medicine has taught Moran that, for some adults, transition can be a "fantastic thing". Yet in 2019, he called for Gids' assessments of Irish children (the country does not have its own clinic for young people) to be immediately terminated, so convinced was he that its processes were "unsafe". The be-kind brigade might also like to consider the role money played in the rise of Gids. By 2020-21, the clinic accounted for a quarter of the trust's income.

But this isn't to say that ideology wasn't also in the air. Another of Barnes's interviewees is Dr Kirsty Entwistle, an experienced clinical psychologist. When she got a job at Gids' Leeds outpost, she told her new colleagues she didn't have a gender identity. "I'm just female," she said. This, she was informed, was transphobic. Barnes is rightly reluctant to ascribe the Gids culture primarily to ideology, but nevertheless, many of the clinicians she interviewed used the same word to describe it: mad.

And who can blame them? After more than 370 pages, I began to feel half mad myself. At times, the world Barnes describes, with its genitalia fashioned from colons and its fierce culture of omertà, feels like some dystopian novel. But it isn't, of course. It really happened, and she has worked bravely and unstintingly to expose it. This is what journ*lism is for.

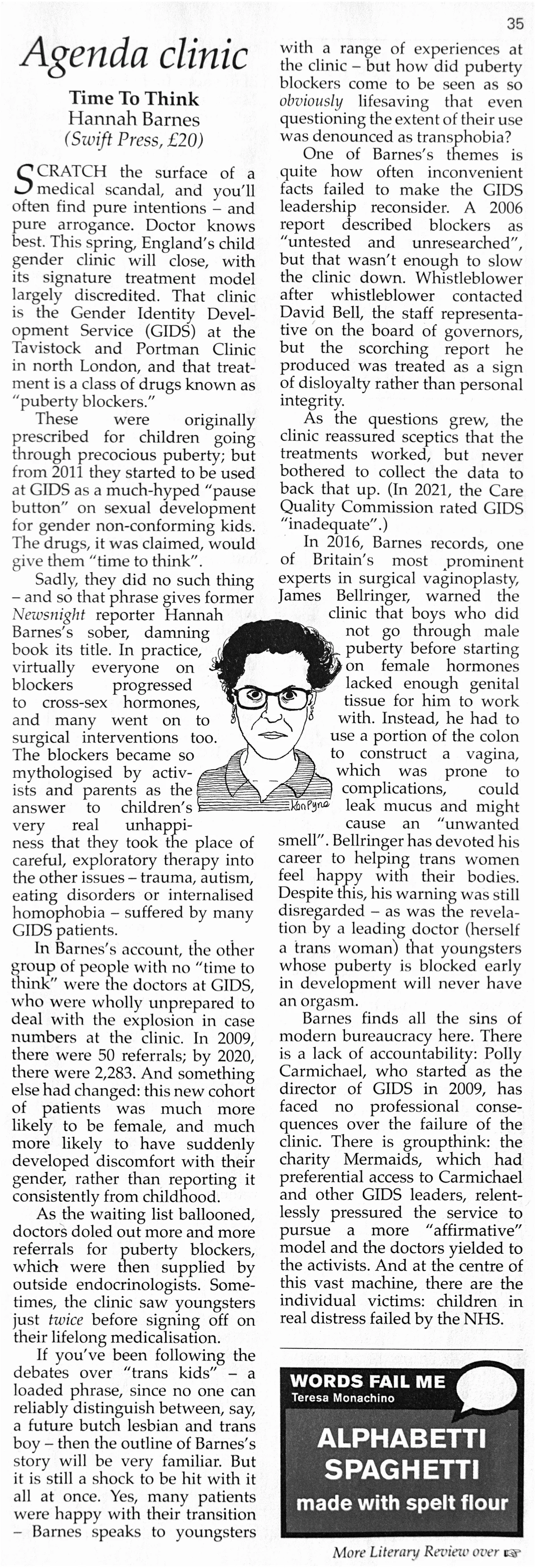

Private Eye

February 17 2023 (No 1592)

Check the rest yourself I got lazy

The Australian, by Christine Middap

February 17 2023, How spotlight shone on a gender crisis in Britain | The Australian

The Times, by Janice Turner

February 14 2023, Time to Think by Hannah Barnes review --- exposing the collapse of Tavistock's gender clinic

The Telegraph, by Suzanne Moore

February 14 2013, Time to Think review: the book that tells the full story of the Tavistock's trans scandal

The Daily Mail, by Sarah Vine

February 14 2023, SARAH VINE: The Tavistock scandal shows what happens when debate is stifled

The Spectator, by Julie Bindel

February 13 2023, How did the Tavistock gender scandal unfold?

Jump in the discussion.

No email address required.

Mental what these people did to kids.

Jump in the discussion.

No email address required.

According to them, those kids were asking for it.

Jump in the discussion.

No email address required.

More options

Context

More options

Context

This is horrible. How can I exploit it?

Jump in the discussion.

No email address required.

https://x.com/Jefflez/status/1627248920098385921?s=20

Jump in the discussion.

No email address required.

https://x.com/guardian/status/1627224515150245888?s=20

Jump in the discussion.

No email address required.

More options

Context

More options

Context

More options

Context

Snapshots:

A modern medical scandal: What really went wrong at the UK's controversial Tavistock gender clinic? - Independent.ie:

https://web.archive.org/https://www.independent.ie/entertainment/books/book-reviews/a-modern-medical-scandal-what-really-went-wrong-at-the-uks-controversial-tavistock-gender-clinic-42347494.html

https://ghostarchive.org/search?term=https://www.independent.ie/entertainment/books/book-reviews/a-modern-medical-scandal-what-really-went-wrong-at-the-uks-controversial-tavistock-gender-clinic-42347494.html

https://archive.ph/?url=https://www.independent.ie/entertainment/books/book-reviews/a-modern-medical-scandal-what-really-went-wrong-at-the-uks-controversial-tavistock-gender-clinic-42347494.html&run=1 (click to archive)

Time to Think by Hannah Barnes review -- what went wrong at Gids? | Society books | The Guardian:

https://web.archive.org/https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/feb/19/time-to-think-by-hannah-barnes-review-what-went-wrong-at-gids

https://ghostarchive.org/search?term=https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/feb/19/time-to-think-by-hannah-barnes-review-what-went-wrong-at-gids

https://archive.ph/?url=https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/feb/19/time-to-think-by-hannah-barnes-review-what-went-wrong-at-gids&run=1 (click to archive)

https://web.archive.org/https://i.rdrama.net/images/1684130363279186.webp

https://ghostarchive.org/search?term=https://i.imgur.com/FiT7edh_d.webp?maxwidth=9999&fidelity=grand

https://archive.ph/?url=https://i.imgur.com/FiT7edh_d.webp?maxwidth=9999&fidelity=grand&run=1 (click to archive)

Jump in the discussion.

No email address required.

More options

Context