And by train drama, I mean  , not

, not  stuff. :marseydeception Grab a drink and stuff off your grill, we're going to look at a war that tore the model railroading community apart nearly four decades ago. It was waged for years across countless physical mailing lists, magazines, and proto-internet forums.

stuff. :marseydeception Grab a drink and stuff off your grill, we're going to look at a war that tore the model railroading community apart nearly four decades ago. It was waged for years across countless physical mailing lists, magazines, and proto-internet forums.

First, a background into model railroading. One could make the argument that it was the first true hobby. Sure, things like sewing and fishing had existed for far longer, but those activities have utilitarian purposes. Model railroading, on the other hand, had no practical applications. It evolved out of a bunch of men, living in a world where trains ruled, deciding that they'd like to create and run their own miniature empires. From the moment Lionel discovered they could sell hundreds of thousands of locomotives to kids who wanted to see one run around their Christmas tree, the hobby was off and running. By the early 1950s, 1 in every 5 American men admitted to owning and running a model railroad. It was something you could bring up and discuss in polite conversation. Walt Disney originally envisioned Disneyland as a place for him to show off his collection of large model trains.

Model trains: one thing that NBA stars, Nazis, and the Jersey mob can all appreciate.

Despite its widespread popularity, the hobby was relatively primitive. Most people limited themselves to premade plastic structures, horrendously ugly trains, and were content with a layout consisting of a loop of track on a piece of plywood painted green. Enter the GOAT, the Wizard of Monterrey, the Grand Poo-Bah. John Allen. A probable neurodivergent and professional photographer, he'd inherited a small sum of money from his grandparents in the mid-1930s. Over the next decade, he was able to invest it in such a way that, coupled with the proceeds of the sale of his photography business in 1946, at the age of thirty-three, he could retire to a small bungalow in Monterrey and live off his savings. Unmolested by desires for a wife and family  who banged the cute twinks

who banged the cute twinks  at the local Navy base. His contemporaries occasionally use couched language to hint at such, but the only ones who would know for certain are nonagenarians who probably don't want to acknowledge that homosexuality exists

at the local Navy base. His contemporaries occasionally use couched language to hint at such, but the only ones who would know for certain are nonagenarians who probably don't want to acknowledge that homosexuality exists

Model railroading was very much an abecedarian hobby at this point in time. The O gauge Lionel trains that most individuals had grown up with made no pretenses to realism. Knowledge was sporadically shared, most often through the burgeoning imprint of model railroad magazines. Because the hobby ties together so many different facets, you would inevitably end with modelers who could make one part realistic, but would struggle mightily with everything else. John Armstrong was widely regarded as being the first to really stress that model railroad layouts could be designed to accommodate realistic operations of a prototype railroad instead of the traditional loop on a table. Even then, he was content to using an incredibly unnatural third rail on his own layout for the ease of electrical wiring. Frank Ellison had a vision for what a model railroad could be, but he was regrettably unskilled as a structure modeler, being content to limit himself to painted buildings on flat wood, like a stage show. Constrained by time, money, and talent, individuals would build a model railroad that was excellent in one aspect but undeniably amateur in others.

This is where John Allen would stand apart. He had nothing but time and resources, and he'd decided to be the first to build a truly functioning world in miniature. He would build every locomotive, car, and structure on the railroad to an exacting degree of realism. He would place them all into scenery also designed to be indistinguishable from the real world. He would master and innovate in electronics and wiring as never before done. All of this would be done in service of creating a model railroad that would operate as a prototype of a real railroad.

At this task, he succeeded as no one had before. Burdened by nothing but free time, he did indeed become a master at making a model railroad. Word spread, and soon he was as close to the face of the hobby as possible. His skills as a photographer also proved to be handy, as far better than anyone before he could capture the results of his techniques and disseminate them through these magazines. Consequently, he became highly valued as a contributor to them all, and the magazines would proudly boast on the cover whenever a John Allen-authored article was contained within. For a time, his legend grew and his word was god.

Sadly, the god of the world of the Gorre and Daphetid was not an immortal deity. A self-proclaimed sloth, he was always portly and never the best physical specimen, presaging the fat nerds of today. Some three decades after he retired to begin his work, a few months before his sixtieth birthday, he died of a heart attack. The railroad lasted for less than two weeks more. After a memorial gathering at his house attended by close friends, someone left on a heater that John had never used. It ignited material around it, and the layout was destroyed by the subsequent fire.

The one surviving locomotive from the fire.

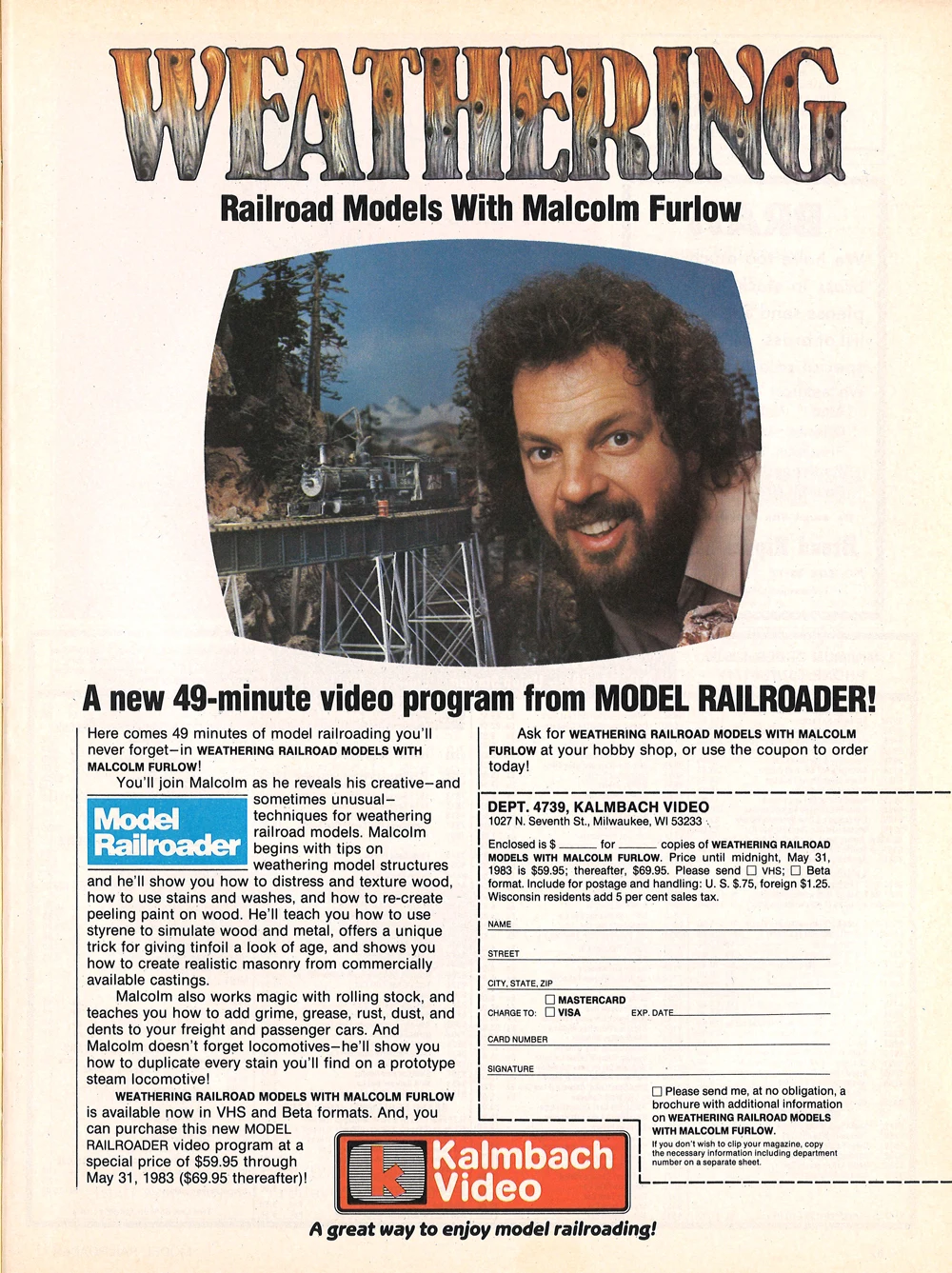

And thus the stage is set for conflict. :: With the elder statesman of the hobby dead, the magazines that had come to depend on his work and wisdom searched for a new torch holder. Enter the focus of this effortpost, Malcolm Furlow. Malcolm had not grown up with an interest in trains or models. Hailing from the southwest, he was a professional artist. He'd spent a number of years working for Disney ::, helping to design their theme parks. And now, he decided that model railroads would be his new medium of choice.

He came onto the scene right when the hobby press was looking for a flagship name. They needed someone who could regularly provide them with dramatic images to include with their articles and on their covers, and he was primed to deliver. Almost from the get-go, photographs of what he was modeling would regularly grace the pages of these publications.

Although from the very start images such as this would draw the first grumblings, as it represented something that no railroad in the world would ever have built, a clearly stylized interpretation of a western mining town, with an absurd retaining wall and confusing arrangement of railroading implements, even his detractors would concede that he had an artist's touch and eye for detail. Photographs of his work sold magazines, much as a busty redhead on the cover of Playboy does. Hobbyists wanted to replicate his techniques, and what he wrote was getting compiled into VHS tapes that you could buy and follow along with at home.

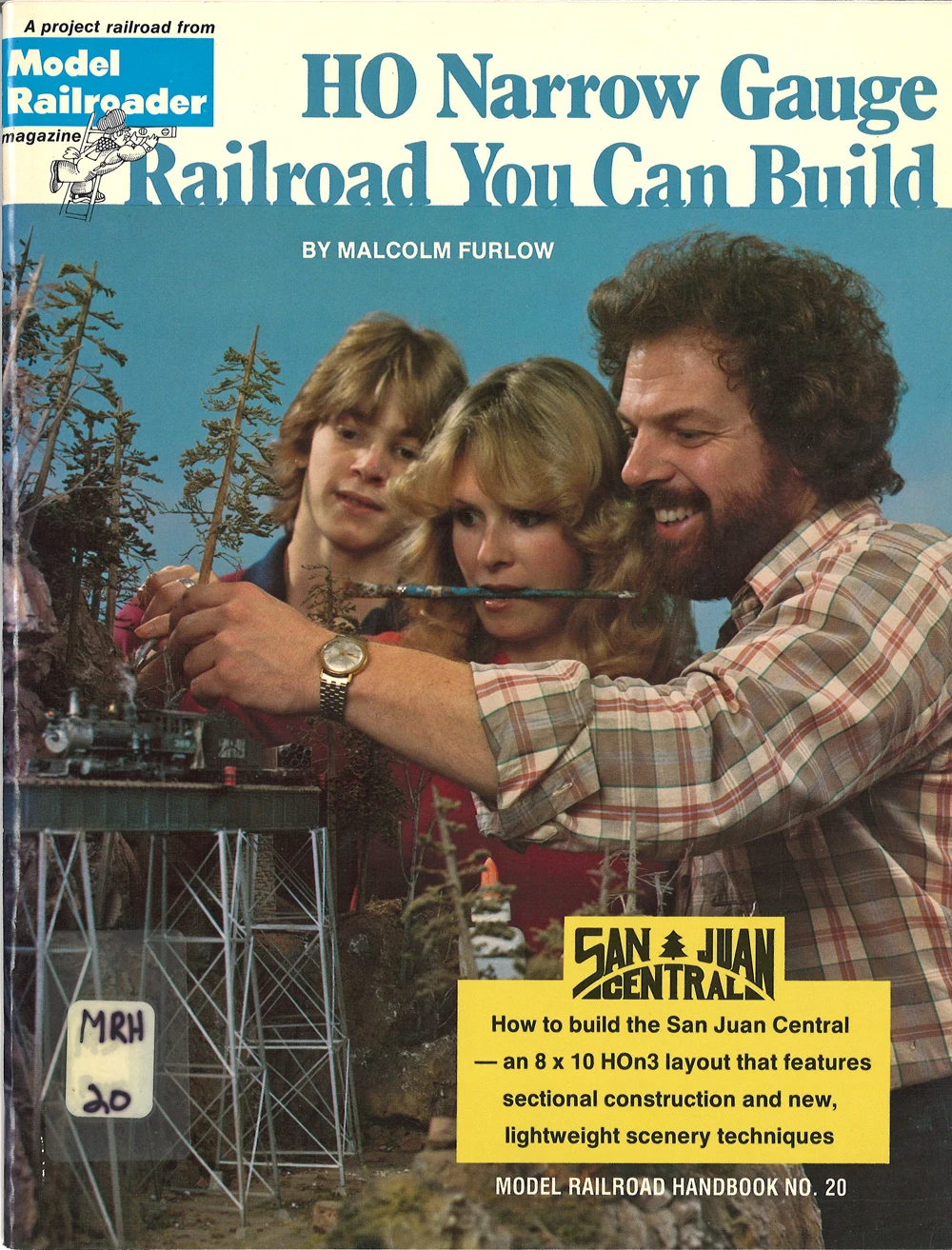

In 1983, it was announced that the trade press was giving him potentially the most responsibility of anyone in the hobby. The most popular magazine, the inventively named Model Railroader, had chosen him to design and build the next project layout. Every few years, they would create one of these features. Over the span of a year, readers would get to follow along and see, step-by-step, how a model railroad is made. They serve as a centerpiece for the hobby, and for many readers, either those new to the hobby or those who have been in for a few years and wish to progress to more than trains running in loops on a painted sheet of plywood, they are the most important part of their hobby development. Written in a "you can do this too" style, the expectation is that thousands of readers, in whole or in part, will follow along with your every word and replicate what is done on the page.

Readers reported being overwhelmed by the amount of work they had to do in following Furlow's techniques for building scenery and structures. Most concerning was the layout itself. Furlow had designed the track plan with a desire to create interesting visual impressions first and foremost. As such, he ignored conventional wisdom about practical design. The layout was constructed with track switches out of reach of any operator and would have required careful planning or extremely long limbs to even build parts of it. Model trains require minimum curve radii to not derail, and he pushed the limits in terms of tightness here. There are ways to circumvent these problems that an experienced modeler would know, but for the targeted audience they would be hugely problematic. Furthermore, given that he was the one writing the series, he focused on his strengths and ignored his weaknesses, namely a complete lack of the technical side of the hobby, such as the electrical work necessary to run trains. This is often the most difficult thing for amateurs to do, and he completely hand-waved past it in his articles. Following his advice would teach you how to paint mountains and weather rolling stock, but you wouldn't learn how to do even the most basic of wiring.

Even if one could get past these hurdles and make the railroad functional, it turns out it wasn't fun to operate, something that anyone with a modicum of experience in designing track plans would have called out early on. The layout was great for photoshoots but not great for actually running trains. Given the ability to do things with your completed models has long been recognized as what sets model trains apart from model boats and planes, this was a serious flaw.

The San Juan Central. Probably not functioning.

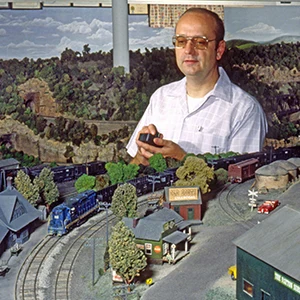

And now, from stage right, enters Furlow's foil, Tony Koestler. A model railroader from an early age and an electrical engineer by trade, Koestler was as fastidious and scientific  as Furlow was not. By day, he worked for Bell Laboratories, working as an editor for their technical publications and telecommunication journals. In his free time, he utilized his experience to gradually insert himself into the model railroad magazines, first as a volunteer contributor of opinion pieces and then as an assistant editor. He was eventually granted a monthly column, and he used this to expound upon his vision of the hobby.

as Furlow was not. By day, he worked for Bell Laboratories, working as an editor for their technical publications and telecommunication journals. In his free time, he utilized his experience to gradually insert himself into the model railroad magazines, first as a volunteer contributor of opinion pieces and then as an assistant editor. He was eventually granted a monthly column, and he used this to expound upon his vision of the hobby.

To Koestler, the purpose of a model railroad was to model a railroad. If you had some magically shrinkray and zapped the Union Pacific with it, that's what you should have in your basement. Much like how coach potato COD players  have rather particular ideas about the niceties of military special forces operations, he had a fervent desire to LARP as an actual railroad employee. Prototypical operation was the only way to do the hobby right in his mind. You shouldn't enjoy speeding trains around a chaotic spaghetti bowl of track. You should enjoy meticulously and ponderously moving a train along a boring, flat, straight section, as in real life. Every time your train dropped off a car along the way, you should stop what you're doing and fill out paperwork documenting the move, just as a real railroad does. Now that's fun. Even better if you have someone else sitting in a corner of the basement, and you have to call him on a radio before you start doing anything.

have rather particular ideas about the niceties of military special forces operations, he had a fervent desire to LARP as an actual railroad employee. Prototypical operation was the only way to do the hobby right in his mind. You shouldn't enjoy speeding trains around a chaotic spaghetti bowl of track. You should enjoy meticulously and ponderously moving a train along a boring, flat, straight section, as in real life. Every time your train dropped off a car along the way, you should stop what you're doing and fill out paperwork documenting the move, just as a real railroad does. Now that's fun. Even better if you have someone else sitting in a corner of the basement, and you have to call him on a radio before you start doing anything.

Normally such opinions would not have carried weight by themselves. The hobby magazines were full of middle-aged men bloviating on tiny trains. In an extreme case of irony, for a man dedicated to realism, Koestler himself was no more than a mediocre craftsman, so he could only sparingly write articles about his own railroad, as such articles required pictures, and the pictures would have revealed a layout that function as a real thing but looked anything but. However, he soon found a kindred soul in Allen McClelland, a man of considerable talents. He had independently developed a taste for extreme operational realism in creating his Virginian and Ohio railroad, and unlike Koestler had a product that looked quite good. Koestler quickly began featuring McClelland's work. Together, with a few other model railroaders, they began to engage in a massive LARP known as the Appalachian Lines. They would fastidiously document a fictional history of a railroad system set in that area of the country, would work together to model parts of it on their respective layouts, and would operate it as a prototype would. Koestler used his editorial power to heavily promote their way of doing things, regularly featuring articles on layouts within this system.

What a stud.

Back on Furlow's side, as the decade progressed, rumblings began to grow about his modeling abilities. Allegations flew that his works were no more than static sculptures or dioramas. Allegedly he couldn't master basic electrical work, and the aforementioned design flaws of his layouts, like the San Juan Central, were such that trains could not be run on them, according to those who visited his Dallas home. For a hobby that's primary purpose is to replicate a functioning railroad, this is disastrous. Even the most cartoonish of Christmas train loops at least moves around the tree. In addition, there were serious allegations that he had burned commercial clients. There are ways for skilled individuals to make money in this hobby. The first is, as mentioned, to write articles for magazines. A second approach is to be hired to build and photograph a company's model kits for their advertisements. A third is to work with the company to design model kits based on your structures. And a final method is to be hired by rich individuals to build a whole layout for them. Furlow was claimed to be doing all four, but he was doing all four quite poorly. Supposedly he had zero sense of time and deadlines. He would constantly miss delivery dates for commissions, ghost and burn clients, and generally just be a flighty, unreliable artist.

As such, private individuals and companies increasingly turned away from him, decreasing his prominence in the hobby. This was all the de facto kingmakers in the hobby, the magazines. Tony Koestler had consolidated his power immensely, being given official editorial status over many of the magazines and books published by the primary hobby imprint Kalmbach.. He would use this as a cudgel, preventing articles about more fantastical forms of model railroading from being run in favor of his grounded, prototype-only approach. Seizing on the commercial disdain for the man, and citing his failure to write certain agreed-upon articles on time, Malcolm Furlow was almost completely blacklisted. Others who would replicate his more fantastical style were likewise discouraged from sharing. Through Koestler's advocacy, Allen McClelland and those who ran railroads under the Appalachian Lines banner were the fare of the day in the trade press. If you picked up a magazine, it would near-exclusively feature how-to articles dedicated to replicating their style. A few exceptions existed, such as George Selios, but he was only afforded print space because his undeniable eye for detail resulted in an incomparable layout.

So, from being a contributor who would appear on the cover of almost every monthly edition in the mid-80s, Furlow gradually was in the press less and less. The breaks became larger and larger and the print space devoted to him smaller and smaller. By the middle of the 90s, he might be featured once a year, and these gaps became larger and larger. His last appearance in the press was in 2003, after the absence of several years, and it was deliberately provocative in its nature.

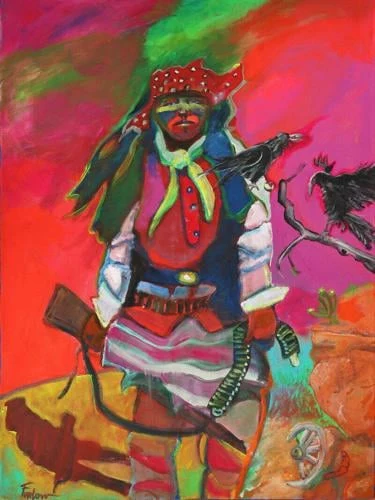

Oh boy

This cacophony of color and overload of objects is peak Furlow. No one could mistake this for a functioning railroad; it's a caricature of the subject. The internet had become the center of focus for discussion, and forums lit up with the vituperations of men in their 50s arguing about it. You can find their words on archived message boards, if you are so inclined. And with that last effort, he disappeared from the hobby. Leaving Texas, he moved to New Mexico and shifted his medium to brightly colored paintings of southwestern life. The Koestler-ites had won.

You can buy his work here

Their victory would eventually prove to be likewise contentious. The model railroad is serious business approach, which had gradually become codified in the hobby press of the 1990s, would prove to turn away newcomers. In person events would be described as hostile, with inane questions asked by these neophytes immediately dismissed. If you didn't have decades of experience with trains and their operations coming into the hobby, you would find yourself ostracized, with very few people willing to help. In what would later be regarded as apostasy, Koestler would even turn his column against John Allen, attacking him for not following Tony's rules of model railroading.

The trade press was likewise unbearable. Written by individuals with such experience, the magazines which once contained basic how-to information had degraded to articles focused on the most obscure of minutia. Want to know how to wire up your first layout so it runs? Not a chance. Want to know how to slightly modify your hand-build signals and electrical blocking so that you can replicate the New York Central's specific way of lighting train routes in 1937 instead of 1939? Yes. Unsurprisingly, the hobby's population began to decline, with fewer and fewer new people joining and the boomers starting to die off. In addition, the rise of other hobbies, predominantly video games, would prove to divert the focus of the slightly neurodivergent white man who had long been the hobby's principle demographic.

The long-term repercussions of this debate echo how the hobby itself has changed. What was once the most popular recreational activity for men in America has declined in interest. There are now countless hobbies for individuals to engage in, and railroads no longer hold preeminence in American life. The neurodivergent rivet-counters and flamboyant artists have gradually been forced to set aside their differences, as there's simply not enough modelers to go around otherwise.

Some twenty years after the war begin, you can find boomers still arguing about Furlow on internet forums. See the various internet threads I linked at the bottom for examples. However, even that fervor faded in all but the most passionate. News of Furlow's death in 2022, allegedly from long COVID, resulted only in respectful tributes and obituaries, even in the magazines that had once called for his head.

Perhaps most emblematic of this approach is the rise of module railroading. Instead of trying to build a layout on their own, modelers will make smaller sections according to certain national standards. At conventions, these sections can then be combined into one large railroad, permitting the running of trains at a scale otherwise impossible. Go to see one today, and you'll see that the modules can and do coexist in harmony, with a hyper-realistic scene of a train crossing the countryside connected seamlessly with one detailing a fantasy landscape. Even the most fastidious of modelers will keep a Thomas or two on their layout. For those dedicated to realistic operations of the Tony Koestler variety, it turns out that most are not nearly as concerned with scenic realism. One can unify a track plan designed for running trains in this way with a more exaggerated and fun environment to run them through, and most clubs now adopt this approach to some degree. Where the old guard would once have zealously guarded prototypical operation as sacrosanct, the current hobby is far more welcoming out of necessity.

In the end, what this conflict boiled down to was the Hegelian dialectic made manifest. Between the thesis that model railroads were artistic endeavors and the antithesis that model railroads are real railroads shrunk down in size, a synthesis has emerged. The truth is that model railroads are simply places for people to create their own worlds and see neat little trains run through them, and that's what the hobby has come to agree on. Fun, with a reasonable element of realism, has prevailed.

ARCHIVAL DRAMA TIME

ARCHIVAL DRAMA TIME

Here's some usenet forums from back it the day. Great to see boomers seethe on 90s internet.

Example

Oh, no! The return of Furlow, the master spammer!!!! I thought we were rid of that parasite for good.

I checked out the website, and part of it's sales-pitch text says,

"Remember, Malcolm was the premier modeler of the early to mid-eighties."

No, he was the premier carpetbagger of theearly to mid-eighties. He was in it only for the money. His track plans were operational voids. Granted, his scenery was exceptional, but limited in scope.

Furlow was drummed out of the hobby for his shameless exploitation of Model Railroader as a free advertising medium.

I guess his career as a "western theme artist" didn't pan out and he's back to try to soak us again...

Hating on Furlow as well as George Selios. Even John Allen catches some.

Furlow gets called a charlaten and carpetbagger.

Is Furlow using Photoshop in 1996 a crime against humanity?

Discussing Furlow's last image from 2003

Furlow Bashing. That's the thread

It's been forty years, and Jannies still have to mop up and lock threads

Jump in the discussion.

No email address required.

OH SHIT I HAVE A PRINT FARM I CAN AFFORD TO GET IN TO MODEL TRAINS WE ARE SO FRICKING BACK

Jump in the discussion.

No email address required.

More options

Context